Written by Paige, edited by Courtland. Note: this post is long, and the email may cut off. We recommend reading in the app.

I’ve been devouring burnout stories. Lately, it feels like everyone’s speaking out about toxic industries and the perils of “lean in” and “girlboss” culture, and I’m here for it. As someone who recently burned out, I need solidarity. I need to know I’m not alone. So after stumbling onto the first, I found myself drawn ever deeper into the memoirs of my fellow burned-out millennials and Gen Xers.1

I love reading their stories, but I’ve noticed many come from people in influential or glamorous jobs. In those narratives, burnout feels almost justified. Of course they worked that hard. Of course they broke. But what about the rest of us? We work just as hard. We burn out too—even without the fancy job.

My career was not “fancy” by any standards. I am a dietitian; or at least, that is how I started. There are no celebrities, and we’re rarely in the public eye. (I mean, has anyone ever seen a TV show about dietitians?) But there was still a ladder to climb, prestige to earn, and titles to chase. The “dream job” I worked my way up to was a public health nutritionist position with a large nutrition assistance program. Like many millennials, I was conditioned to make work my entire identity. And if work is your identity, you can’t stagnate. You have to keep moving—“growing,” but only in the career sense. I suppose it’s no surprise the burnout monster came for me, too.

I started as a young, idealistic dietitian who wanted to make the world a better place. For thirteen years, I worked in health care and public health. I felt compelled to do meaningful work. And my work had to give my life meaning. (“Love your work and you’ll never work a day in your life,” isn’t that what they told us?) I helped patients, solved problems, improved processes, and made positive changes at every job I held. I built relationships with patients and coworkers. I pushed myself to learn as much as I could and always tried to do my best. I knew I wasn’t changing the world, but I felt like I was doing some good.

A decade later, I left my job a jaded, cynical, harangued middle manager. I was firmly stuck in the web of a toxic bureaucracy, my efforts to effect positive change thwarted at every turn, unable to recall why I was there in the first place.

So what happened? How did I get here?

Moving up

If work is your whole identity, then everything you do is in service to your career. Life milestones follow suit, work comes first. I believed it was the only thing that gave me value, the only thing that justified my existence. The phases of my life were dictated. There was always a next step: a degree, an internship, a job, another job, another degree. Work achievements were the only framework I knew for structuring a life.

Early in my career, I worked in a nursing home in a low-income area caring mostly for elderly patients—although some were the same age as me (I was in my 20s). Then I spent a few years as a clinic nutritionist serving participants in a government nutrition program. I also held roles in a university extension program, an international development organization, and a humanitarian aid group. These jobs overlapped, and during that stretch I went back to school to earn my MPH—my second master’s degree—because I needed something more. Without it, how could I do better and do more in my work?

Just before graduating with my MPH in 2019, I became the director of a long-underperforming local nutrition program. I applied while abroad completing my master’s thesis. I didn’t want to take another entry-level position after graduation, and this was a chance to be a director. (Ah, titles.) I told colleagues I’d probably hate it—but I had to try. I remember their confusion when I said this.. Maybe they couldn’t imagine why I'd choose such a thing. But I thought there was nowhere to go but up—even if the path looked miserable.

As it turned out, I didn’t entirely hate it. I managed four clinics, nearly 4,000 clients, and a staff of 15 to 18. We worked to rebuild a flailing program and restore its reputation in the community. When I arrived, the department didn’t even have pens—let alone the humans to use them. Within a few months, I’d filled the positions, restocked supplies, and shored up our finances. We were doing well. I was a person who solved problems. Who got things done. A new piece of my identity clicked into place. That meant something.

And then COVID happened.

For two years, I led our department through the pandemic. Through shortages of masks, gloves, sanitizer, and wipes. Through the fear of showing up to work, not knowing what would happen if we got sick. Through the whiplash of constantly changing directives—reopen, cancel, reopen again. Through a nationwide infant formula shortage layered on top of empty grocery store shelves. And through trying to explain all of it to staff and clients. Now I was a person who made sense of uncertainty. I was adaptable, nimble in a crisis. Another piece of identity slotted into place.

Dream or nightmare?

In 2022, I became a mother. Desperate to get out of daily clinic management (how was I supposed to wake up to callouts and a baby before 6 am?) I took a new job. The dream job. A promotion, essentially, though at another organization. Everything I’d worked for—the identity I’d been building—had led to this.

I could work remotely some of the time! I wasn’t exposed to nearly as many germs! I had more responsibility, a better salary, a cool title! And because this organization oversaw the program I’d spent the last decade in, it felt made for me. My skills, my knowledge, everything I’d worked toward—it was all finally coming together. I could make real changes, on a bigger scale. Maybe even do a little more to make the world a better place. By every measure, this should have been the dream job.

It was a nightmare.

Our workplace culture was toxic. Implicitly, we were forced to “perform” office work—drowning in tasks, wildly understaffed, yet still expected to prove we were busy. If your calendar wasn’t packed to the brim, you must not be working. If you weren’t multitasking—emailing, Teams chatting—during meetings, you must not have enough to do. There was no focus time. No creative time.

Explicitly, we were told not to show our personalities at work. People ate lunch in silence or alone at their desks. Any “fun” we had was scheduled into the PowerPoint deck (as in, we will have fun on slides 20 through 26)2 which, of course, meant it was no fun at all.

The team was suffering. We pulled off major projects without recognition, celebration, or even a pause. We were expected to perform. No matter how many vacancies we had, how deeply funding had been slashed, and despite a global pandemic that had killed people in our program—none of it mattered. Worse, we were expected to do more quarter after quarter, year after year. Work piled up; support lagged. Colleagues left meetings in tears. Some sat paralyzed in their cars each morning, unable to walk inside under the crushing weight of it all.

By July 2023, I hit my breaking point.

I was beyond stressed. I was a changemaker in a place that didn’t want change. I worked endlessly to improve the program—for staff, for clients—but nothing made it through the molasses of the bureaucracy. And instead of getting help clearing a path, my team and I hit more and more barriers. (But I had come here to help people. To make this better for everyone. If I wasn’t doing that—what was I doing?)

And then staff started coming to me with their problems, their burnout, their pain. But I was impotent there, too. I couldn’t help them and I couldn’t help myself.

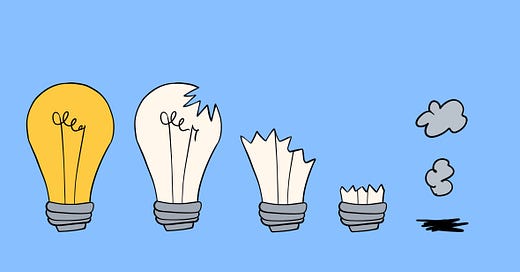

Burn up, burn out

I felt “an unconquerable sense of futility” at work (as Amelia and Emily Nagoski write in Burnout). There’s no better phrase for the feeling. I kept pouring energy into the job, and just...nothing. Every spare thought was hijacked for office problem solving. I commuted listening to workplace improvement podcasts. At night, I scrolled The Cut’s “Ask a Boss,” desperate for anything that might help. My conversations became monotonous, dominated by this or that work issue. (I don’t think I’ve ever been a more boring human.) Even on walks in the woods—normally a refuge—I’d doom loop the same unsolvable problems in my head. I never cracked them. I was completely drained.

They say you can’t pour from an empty cup. I learned that the hard way. Eventually, I realized I couldn’t keep going like this. So I did two things.

First, I sat down with my managers and laid it all out—why the team was unhappy, why things couldn’t go on like this. I told them I’d leave. I was brutally honest. It should have been their reckoning. I guess I still had a glimmer of idealism, because I genuinely believed they'd act. I hoped that if I stepped up and told them what it was like, it would have to make a difference. (Spoiler: it didn’t.)

Second, I applied for a new job—different organization, same program, even more potential. Like a true millennial, I kept going—onward and upward. I moved quickly through the interviews. I clicked with the CEO (my half-hour interview stretched to an hour). They promised a better culture, more family-friendly policies. I thought I’d finally found my out.

I didn’t get the job.

The news came while I was on vacation. I went into the bedroom of our Airbnb, crawled under the covers, and stared into space. I couldn’t fathom going back. The dim gray cubicles. The flood of video calls. The hopeless workload. The despondent coworkers. I pictured pulling into the garage, sitting in the car, feeling the weight of the building above me.

And then it hit me—what was obvious to everyone else (probably you, too). I wasn’t crushed about the door that closed; I was crushed by the one that was still open.

And so I quit. I returned from vacation and gave notice. For the first time in my life, I did not have a plan. (I am fortunate in that my partner can support our family and so I was able to quit without another job lined up.) There was no school, no internship, no next job to dictate my next chunk of time. No framework for how I should move through the world.

Adrift, but in a good way

The abrupt loss of my work-martyr identity hit harder than expected. I’d been so consumed by burnout—so wrapped up in the drama of leaving—that I hadn’t seen this part coming. Even a toxic job is a mooring, and I left without a destination. I was adrift. Suddenly, I was untethered not just from a job but from my career, my purpose, my sense of self.

“That’s what happens when we don’t talk about work as work, but as pursuing a passion." writes Anne Helen Petersen in Can’t Even. "It makes quitting a job that relentlessly exploited you feel like giving up on yourself, instead of what it really is: advocating, for the first time in a long time, for your own needs.” (p. 86).

But I didn’t know how to advocate for my own needs. I didn't have boundaries. I was so used to being exploited (exploiting myself?)—for the cause, for the mission, for the greater good. And now there was this void. A hole in my identity. Whole stretches of time suddenly empty of “purpose.”

I spent my first week of freedom taking long walks in the forest near my house. I breathed in the scent of the trees. I listened to the stream bubbling, the birds chirping, the insects buzzing. My sneakers crunched on the path. I saw deer munching on foliage. I marveled: I’m not in my office. I’m in the real world. It felt wild. I was free.

Never again would I have to sit through Zoom calls with a frantic Teams chat running alongside, or keep banging my head against the futility of fixing things that didn’t want fixing. But in a cruel twist, even out in the woods, my brain kept churning. The work problems kept looping. I ran endless scripts in the background, searching for solutions that would never come. I was trying so hard to feel something, and work (not even my work anymore) kept showing up.

At some point, the scripts began to fade, and I started daydreaming again. How great would it have been if that had happened the first week? It had been so long since the creative part of my brain had the space to turn on, since I had the freedom to zone out and find flow.

Looking back, I feel two losses deeply. One: the heartbreaking loss of my daydreams, which once came easy and felt endless. And two: that I didn’t even notice they were gone until they came back.

I had traded my dreams for a job. Burned myself out for a nightmare. I was numb.

One year later

I wrote these words in 2024, one year after leaving that job, trying to make sense of how I could have been so thoughtful—and still so obviously wrong. This reflection is just the first few chapters; I’m still in the middle of it.

It took half a year to get past the worst of the burnout and begin piecing together a new identity. Even now, nearly two years later, I’m not exactly sure who I am or what I like without a job to anchor me. I still don’t have a “track.” I’m not sure what I want to do next. But I’ve found new ways to be of service, to make meaning. And I know now: it doesn’t have to come from my job.

I’ll write more about my recovery from burnout as this newsletter grows and matures. For now, I’ll leave you with this:

When I told people I had just left a toxic job, burned out, done—everyone said, “Congratulations.” No one gave a shit about my job or my title. None of my friends or family saw me as incomplete without work. They just saw me: happier, less stressed, more at peace, more present, better rested, and more even-tempered than I’ve ever been.

I finally see that version of me, too.

Great reads on this topic: Ambition Monster (by Jennifer Romolini), and The Myth of Making It: A Workplace Reckoning (by Samhita Mukhopadhyay).

This is not an exaggeration.

![The [Disaffected] Millennials Club](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!AYOy!,w_80,h_80,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fd2c688f0-423b-4724-84de-0d14ad414518_1280x1280.png)

![The [Disaffected] Millennials Club](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!AYOy!,w_36,h_36,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fd2c688f0-423b-4724-84de-0d14ad414518_1280x1280.png)

Oof this is so relatable. Thanks for putting into words what I’ve been feeling for so long. I’m on the edge of my seat to read more about your journey. Looking forward to the next installment.